|

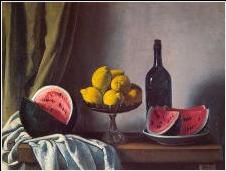

1947. Bodegón, Oil /canvas (67 x 90 cm). |

|

THE WORK OF ALBERTO DUCE. LIVE NATURE

Alberto Duce was notably a figurative artist; his productions include religious topics, landscapes, stills, portraits and mainly compositions in which the argument surrounds the human figure. These compositions go from those whose characters are regional and popular figures to others portrayed by nudes and semi-nude or feminine figures dressed with classic tunics; a characteristic that he maintained in drawing, as in engraving and painting.

The topic preferred by Duce was the feminine nude, understanding it as the maximum expression of beauty: I am interested in the forms, especially the human forms, to express the concept that one has of the beauty, to capture the vision of the world, of life. (Aragon Herald, Zaragoza, 28-08-1977). According to the thesis sustained by art historians such as Kenneth Clark gThe Nude: A Study in Ideal Formh 1956 or Linda Nead gThe Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexualityh 1988 the feminine body is not only another topic in art and western aesthetics, but rather it is an art form that should be recognized as a particularly significant reason in the history of our visual culture. And, indeed, if we make a shallow review of the history, we see that the classics used it almost with exclusivity, and that the medieval imagery was not able to make it disappear. Just by taking a look at many of our Roman churches - and starting from the Renaissance its reproduction had no rival. We have to arrive to the present, and it is after the victory of abstract painting, when the nude - the same as with the rest of the live and inert nature - begins to become a less motivational topic for the artists.

However, although it is true that during the second half of the 20th century the artistic non figurative productions seem to gain in volume of exhibitions and sales over the figurative ones, it is also true that the new realisms continued to be inspired by the human body as the motif of their works. We canft forget the massive extent of the publicity and the use of the body, especially the women's, as a visual lure.

On the other hand, and simultaneously with the success of the non figurative painting, we have the paradox that the "topic" or "motif" of the nude becomes the attraction for the art specialists and critics as it probably had never been before. Certainly, in the spring of 1953 the English historian sir Kenneth Clark held six conferences about the artistic nude in the A. W. Mellon Courses of Fine arts, in the National Gallery of Art of Washington, reaching such success that he was forced to broaden his investigations and to publish them under the title The Nude: A Study of Ideal Art (London, 1956). His first Spanish edition in gAlianzah, gEl desnudoh, was almost thirty years later (1981)! In this work he tells us that prior to this study there were in only two general studies of some value on the topic: Die menschliche Gestalt in der Geschichte der Kunst (1903) by Julius Lange and Der nackte Mensch (1913) by Wilhelm Hausenstein. In the lapsed time since ClarkLs work saw the light for the first time until now numerous publications related with the feminine and masculine nude have been published and there have also been numerous exhibitions on the same topic.

Returning to DuceLs production, it is necessary to say that his figures are based on the observation of the natural; each work, whether a still life or a composition with diverse figures, is a recreation of nature, reproducing the forms and recreating the material qualities. For that, he counts on his mastering of the line, of the drawing: The drawing is the support, the architecture of the color. Even when the drawing is not manifested in an obvious way, the drawing is always present, even in the masses of color. The drawing, furthermore, is something that is not improvised. It needs the discipline of many years. On the other hand, color is a more intuitive thing, of sensibility, and it is manifested in an imponderable way. (Aragon Herald, Zaragoza, 23-05-1971). From there his studied pictorial or graphic compositions, of great technical perfection, of exquisite foreshortenings, daring and devious, that a master could only trace. The feminine studies, faithful to the originals, sometimes present even the pubic hair - parts of the body generally avoided by most of the non hyper-realistic artists - that ends up evolving in the way it is interpreted, going from the abstractions of the forties to the naturalisms of the sixties and later.

The figures, traced by means of an incision in the paste or in the metal, or with a fine line on the paper, are of concise profile, exempt of leaning lines, and form compositions in intimate settings, where an atmosphere of complicity is created, shared by two or three people, usually women, and where the architectures or the objects, a chess board, some dice or an easel, are nothing more than an excuse to place the bodies and to create the space. On many occasions, stills and landscapes scarce of trees that give cover to the figures and frame the scenes are usually incorporated in the canvas or in the metal, next to the bodies, complementing the composition. This is achieved following a mathematical architecture of the space, where the volumes are geometrically distributed forming images where the light and the pictorial matter (or in the case of the engraving, the aquatint and the marks of the acid on the metal) suggest qualities and determine figures. In any case, the images offer lyricism and sensuality that escape in spite of the line that seeks to tie them. Sometimes, the body traced reaches formulations of erotic insinuation.

Alberto Duce remained faithful to himself and, although he could have been appointed to the consecutive "-isms" he saw begin to grow and succeed throughout his life, he never stopped practicing the artistic principles learned in his youth, nor stopped producing works according to his particular vision of what the world should be; which, with the exception of the works that denounce the Vietnam war, they are always of a friendly nature. Some of his thoughts illustrate what he thought about the artist and his activity: There is excessive hurry. For art, this is not good. There is an immediate need to exhibit, to sell, to see his name in print. (...) The artist should, at all times, return toward himself, forget when possible, and overcome the determining factors of the moment. To contain oneself after having observed and offered their work to society, but from oneself, from his experiences, not from society, from the fashions, or the economies. (Aragon Herald, Zaragoza, 28-12-1975)

DuceLs formation was academic and he assimilated, besides the knowledge of the graphical and pictorial techniques, the classic ideal of beauty. In his works we can appreciate the Aristotelian statement... gThe supreme forms of the beauty are the order, the proportion and the boundaries, that the mathematical sciences manifest in supreme degree. And since these (I refer, for example to the order and boundaries) are, clearly causes of many things, it is evident that they speak in certain way of this cause, the cause of the Beauty." Aristotle: Metaphysics, XIII Book, Ed. Gredos, 1994, pg.514. |

|

1987. Pintor y modelos. Mixed technique / canvas (115 x 146 cm). |

|

1943. Aragonesa.. Oil /canvas (62x 48 cm). |

|

1945. La Santa Faz. Oil /canvas (80 x 100 cm). |

|

1945. Academia. Oil /canvas (100 x 80 cm) |

|

1948-49 Baile. Lithograph (23 x 31 cm). |

|

1966. Concierto. Mixed techique / canvas (150x200 cm). |

|

1982. Composición. Oil / board (17 x 23 cm). |

|

1969. Víctimas inocentes. Mixed technique/ canvas (146 x 195 cm). |

|

2000. Concierto. Oil/canvas (97 x 162 cm). |

|

Circa 1952 Square dancing. Pencil and watercolors / paper (44 x 64 cm). |